When GCs Should Call Independent Counsel: Joint Venture Representation

LATEST NEWS

COVID-19 Testing Of Non-Emergent Patients Seeking Non-Covid-19 Care, Elective Surgery Or Elective Procedures: Standard Of Care And Liability Risks

Two questions were posted on an American Health Law Association listserv as follows: “Not all hospitals and ASCs are testing patients before surgical procedures. What is the standard of care? Are these facilities potentially liable for risk to health care providers...

Physicians and Hospitals Criticized for Hoarding and Illegal Prescribing of Unproven Coronavirus Treatments

Physicians and hospitals criticized for hoarding and illegal prescribing of unproven coronavirus treatments; State pharmacy boards respond by issuing rules to curtail use of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as a preventative and to ensure availability for lupus and...

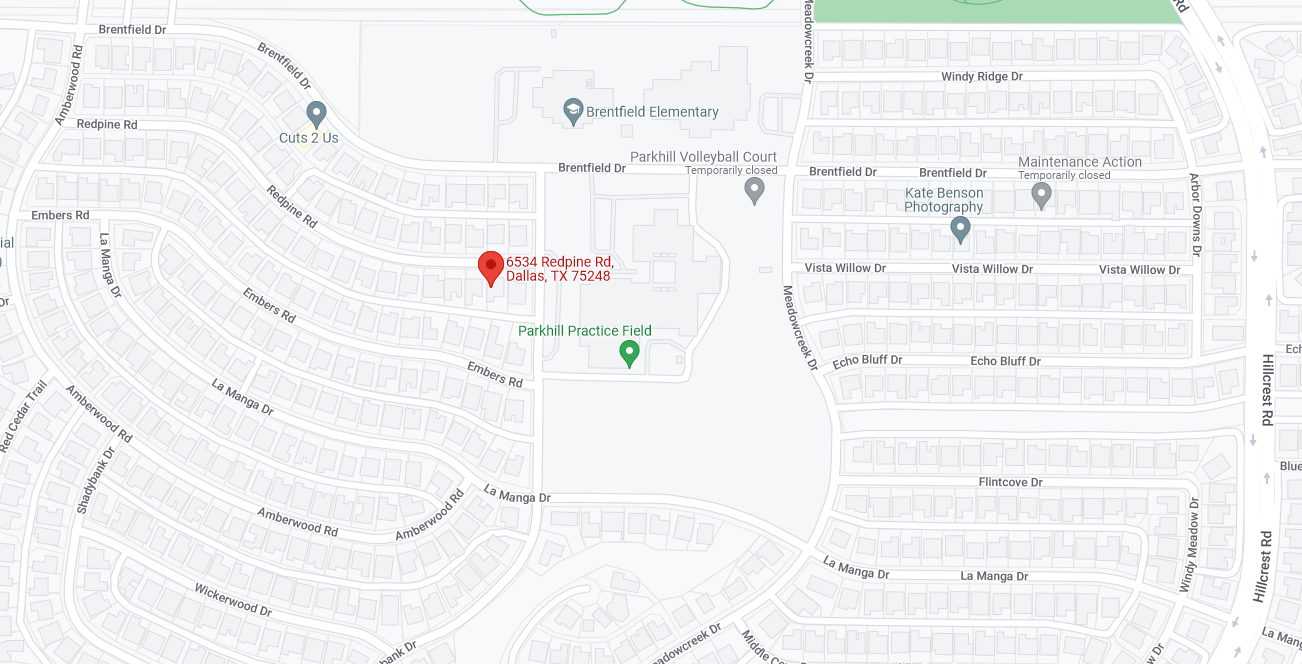

Bridal Shop’s Ebola Claim Fails Against Dallas Hospital

The Supreme Court of Texas has dismissed an Ohio bridal shop's negligence claim against a Dallas hospital for allowing a nurse who had been exposed to the Ebola virus to visit the shop leading to its closing.[1] The court ruled the claim was a "health care liability...

Are There Texas Rules On EE/IC Misclassification?

The employee/independent contractor misclassification question above was asked as part of a Q&A in a nationally published guide to Texas employment laws and rules. The answer was “Generally, no.” from a labor and employment law firm with several Texas offices....

Physician Employment Contracts Troublesome Terms Whether Starting or Continuing A Medical Career

For graduating residents and fellows, their first physician employment contract may be received with emotions of joy and trepidation. The contract is typically lengthy, contains multiple restrictions on the physician’s practice of medicine, and legally complex.

CONTACT LEW

THE OFFICE

Healthcare joint ventures today proliferate as an operating structure for hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers, cancer treatment centers and other healthcare entities. Contractual JVs between healthcare management companies and physician practices for new ancillary healthcare services are also common. In-house counsel of the JV’s majority owner typically control the JV’s legal work from its establishment and throughout its existence. Tasks include ensuring the joint venture adopts and complies with policies and procedures that are appropriate and consistent with the operations of the majority owner. While convenient and efficient, this approach to legal representation raises ethical issues and potential disciplinary action if in-house/outside counsel only represent the majority owner’s interests and do not act on behalf of the other clients during JV formation, or on behalf of the joint venture itself upon its roll-out.

Attorneys, whether in-house or in private practice, have duties of loyalty, independent professional judgement and confidentiality to each client when multiple or joint clients are represented. These duties must be exercised in an impartial manner, even when conflicts arise. Business rivalries, personal differences or material and adverse conflicts may necessitate withdrawal and use of independent counsel for representation of joint ventures.

Drafting a Joint Venture Agreement – Multiple Party Representation

In many healthcare joint ventures, the majority owner’s counsel (in-house or outside) drafts the joint venture agreement. At this stage, there may be no perceived conflicts among the multiple parties. Common representation may be permissible where the pre-JV clients are generally aligned in interest even though there is some difference of interest among them. While such an arrangement may occur without problems, the potential for current-client conflicts exists and should be considered by the parties.

The Texas Disciplinary Rules for Professional Conduct (TDRPC), Rule 1.06: Conflict of Interest: General Rule, generally provides a lawyer shall not represent multiple parties in a joint venture if the representation:

- Involves a substantially related matter in which one client’s interests are materially and directly adverse to the interests of another client of the lawyer or the lawyer’s firm (or in-house legal department); or

- Reasonably appears to be or become adversely limited by the lawyer’s or law firm’s responsibilities to another client or to a third person or by the lawyer’s or law firm’s own interests;

Except, a lawyer may represent multiple clients in the circumstances described above if:

- The lawyer reasonably believes the representation of each client will not be materially affected; and

- Each affected or potentially affected client consents to such representation after full disclosure of the existence, nature, implications, and possible adverse consequences of the common representation and the advantages involved, if any.

What does this mean for the attorney drafting the joint venture agreement? What is the meaning of directly adverse? Adversely limited? In Comment 6 to TDRPC 1.06, the representation of one client is identified as directly adverse to the representation of another client if the lawyer’s independent judgment on behalf of a client, or the lawyer’s ability to consider, recommend or carry out a course of action, will be or is reasonably likely to be adversely affected by the lawyer’s representation of, or responsibilities to, the other client.

A lawyer may not represent multiple parties to a negotiation if their interests are fundamentally antagonistic to each. The Texas position for an impermissible conflict of interest existing before representation is undertaken is clear – the representation should be declined. If the conflict arises after representation has commenced, the lawyer must take effective action to eliminate the conflict, including withdrawal from representation if necessary.

According to comments to Model Rule 1.7 of the American Bar Association’s (ABA) Model Rules of Professional Conduct, a conflict of interest exists, in the absence of direct adversity, if there is a significant risk that a lawyer’s ability to consider, recommend or carry out an appropriate course of conduct for the client will be materially limited as a result of the lawyer’s other responsibilities. Consequently, a lawyer may be adversely limited by:

- His responsibility to keep confidential certain information of one of the multiple clients, or

- A personal relationship with a client that interferes with or adversely affects his independent professional judgment.

Drafting a joint venture agreement for multiple parties is an instance identified by comments to Model Rule 1.7 where a lawyer is likely to be materially limited in the lawyer’s ability to recommend or advocate all possible positions that each client might take because of the lawyer’s duty of loyalty. (FYI — Federal courts in Texas may apply the stricter ABA’s Model Rules over the more permissive TDRPC’s professional conduct rules.)

The TDRPC recognizes that conflicts of interest in non-litigation matters may be more difficult to assess for direct adversity. According to Comments 13 and 14 to TDRPC 1.06, relevant factors for determining whether there is a potential for adverse effect in a non-litigation matter (measured by proximity and degree) include the:

- Duration and intimacy of the lawyer’s relationship with the clients involved,

- Functions performed by the lawyer,

- Likelihood that actual conflict will arise, and

- Likely prejudice to the client from the conflict if it does arise.

Compared to the comments of the Model Rules, the TDRPC comments are more permissive with respect to drafting of joint venture agreements by counsel to the majority owner. However, where essential components, such as loyalty, of a multiple client relationship are threatened, application of the Model Rule over the TDRPC may be necessary.

According to the federal district court for northern Texas in Galderma Laboratories LP v. Actavis Mid Atlantic (2/22/2013) denying motion to disqualify Vinson & Elkins from representation, full disclosure and informed consent are the cornerstone of the ABA standard for multiple client representation. Informed consent requires a lawyer to have communicated adequate information and explanation about the material risks of and reasonable available alternatives to the proposed course of conduct. Model Rule 1.7 requires lawyers to advise clients regarding all conflicts or potential conflicts in relationship to the lawyer’s representation of the client’s interests and how they could affect the lawyer’s exercise of independent professional judgment for the clients. The Model Rule is strict and requires written disclosure of material risks and alternative courses of action for fully informed consent of less sophisticated clients. On a pre-engagement basis through written communications in offering memoranda, subscription agreements or separate consent documents, the effects of multiple representation should be discussed.

In contrast, TDRPC Rule 1.06 permits a client under some circumstances to consent to multiple representation regardless of a conflict or potential conflict. When more than one client is involved, the question of conflict must resolved as to each client. Comment 8 identifies disclosure and a written summary of the considerations disclosed as necessary for the fully informed consent of less sophisticated clients. Consent in writing is not required.

However, an in-house or outside counsel that has properly undertaken multiple representation may be confronted subsequently by a dispute among the clients with regard to a matter in which he represented the majority owner. Counsel is forbidden by the Texas Rule 1.06 from representing any of the parties in regard to that dispute unless informed consent is obtained from all of the parties to the dispute represented by the lawyer.

Representing the Joint Venture – Joint Party Representation

Once a joint venture is formed and operating, the health care system or management company, as majority owner, usually directs its in-house counsel (or outside counsel) to provide legal services to the JV. May an in-house counsel of a health care system represent a joint venture in which the system is a venturer without violating TDRPC 1.06?

This question was addressed in Opinion 512 (1995) of the Texas Supreme Court Professionalism Committee. Opinion 512 considered a corporation venturer that “loaned” its in-house lawyer to the joint venture to provide legal services to the JV. The corporation would be reimbursed by the JV for the costs of providing the lawyer. The opinion declared that “loaned” in-house counsel must recognize the joint venture is his client and that loyalty is an essential element of the relationship with his client. According to Opinion 512, potential conflict does not arise by virtue of the extent of control or ownership that the corporation has in the JV, or because the corporation charges or does not charge an amount for providing the in-house lawyer. Instead, it is the simultaneous representation of the joint venture and the corporation that presents the potential for conflict under TDRPC 1.06.

Even though a conflict, or potential conflict, may exist due to such simultaneous representation, such joint representation is permissible if there is compliance with TDRPC 1.06 as follows:

- The in-house lawyer must reasonably believe that the representation or each client will not be materially affected and the corporation and the JV must consent to such representation after full disclosure.

- The required consent may not be given on behalf of the JV by the corporation employing the lawyer, but must be obtained from an authorized employee of the joint venture, if it has its own employees, or from the other joint venturers.

- The disclosure and consent should include the payment arrangement between the joint venture and the corporation for the legal services of the in-house counsel.

- If a potential or actual conflict develops into an impermissible conflict, the “loaned” in-house attorney should withdraw.

What are impermissible conflicts for a healthcare joint venture? A lawyer cannot engage in a representation when there is a significant risk the representation will materially limit representation of the other client. Such challenges may face the in-house lawyer if he has non-legal responsibilities for one or both clients, or if there are financial disincentives to accessing outside counsel. As either his employer or the JV grows in complexity, his duties may expand and reduce his access to a client. The in-house counsel has dual roles with attorney-client privilege protection and must be certain that the privilege will cover his communications between his employer and the joint venture. When the majority owner owns a controlling interest in the JV, the in-house counsel is considered an agent for the JV. Both the joint client doctrine and the common interest doctrine may be useful for protecting the sharing of privileged information.

When should the general counsel consider engaging independent counsel for the joint venture? Internal investigations, medical peer review, JV business opportunities that overlap with the majority owner’s business and JV transactions are all matters in which independence of the lawyer may be appropriate, if not crucial, to the process and outcome. If there is potential that the in-house counsel’s judgment is or appears to be compromised as a result of relationships with the joint venture’s management, employees or otherwise, in-house counsel should be withdrawn and replaced by independent counsel. Unintended results may demonstrate the need for independent counsel. For example, a third party’s demand for all of an in-house counsel’s internal communications with his employer regarding an investigation, transaction or other sensitive matter becomes problematical if the attorney-client privilege has been waived as to the joint venture through joint representation by a “loaned” in-house counsel.

© Copyright 2024

Designed by StarFlame Solutions, LLC